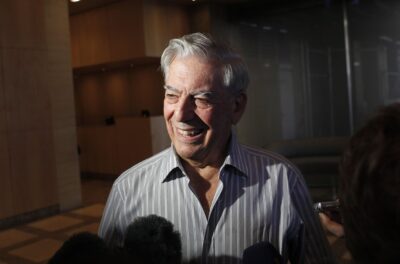

Mario Vargas Llosa, Peruvian author and Nobel literature laureate, dies at 89

By Canadian Press on April 13, 2025.

LIMA, Peru (AP) — Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa, Nobel literature laureate and a giant of Latin American letters for many decades, has died, his son said Sunday. He was 89.

“It is with deep sorrow that we announce that our father, Mario Vargas Llosa, passed away peacefully in Lima today, surrounded by his family,” read a letter signed by his children Álvaro, Gonzalo and Morgana, and posted by Álvaro on X.

The letter says that his remains will be cremated and that there won’t be any public ceremony.

“His departure will sadden his relatives, his friends and his readers around the world, but we hope that they will find comfort, as we do, in the fact that he enjoyed a long, adventurous and fruitful life, and leaves behind him a body of work that will outlive him,” they added.

He was author of such celebrated novels as “The Time of the Hero” (La Ciudad y los Perros) and “Feast of the Goat.”

A prolific novelist and essayist and winner of myriad prizes, Vargas Llosa was awarded the Nobel in 2010 after being considered a contender for many years.

Vargas Llosa published his first collection of stories “The Cubs and Other Stories” (Los Jefes) in 1959. But he burst onto the literary stage in 1963 with his groundbreaking debut novel “The Time of the Hero,” a book that drew on his experiences at a Peruvian military academy and angered the country’s military. A thousand copies of the novel were burned by military authorities, with some generals calling the book false and Vargas Llosa a communist.

That, and subsequent novels such as “Conversation in the Cathedral,” (Conversación en la Catedral) in 1969, quickly established Vargas Llosa as one of the leaders of the so-called “Boom,” or new wave of Latin American writers of the 1960s and 1970s, alongside Gabriel García Márquez and Carlos Fuentes.

Vargas Llosa started writing early, and at 15 was a part-time crime reporter for La Crónica newspaper. According to his official website, other jobs he had included revising names on cemetery tombs in Peru, working as a teacher in the Berlitz school in Paris and briefly on the Spanish desk at Agence France-Presse in Paris.

He continued publishing articles in the press for most of his life, most notably in a twice-monthly political opinion column titled “Piedra de Toque” (Touchstones) that was printed in several newspapers.

Vargas Llosa came to be a fierce defender of personal and economic liberties, gradually edging away from his communism-linked past, and regularly attacked Latin American leftist leaders he viewed as dictators.

Although an early supporter of the Cuban revolution led by Fidel Castro, he later grew disillusioned and denounced Castro’s Cuba. By 1980, he said he no longer believed in socialism as a solution for developing nations.

In a famous incident in Mexico City in 1976, Vargas Llosa punched fellow Nobel Prize winner and ex-friend García Márquez, whom he later ridiculed as “Castro’s courtesan.” It was never clear whether the fight was over politics or a personal dispute, as neither writer ever wanted to discuss it publicly.

As he slowly turned his political trajectory toward free-market conservatism, Vargas Llosa lost the support of many of his Latin American literary contemporaries and attracted much criticism even from admirers of his work.

Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa was born March 28, 1936, in Peru’s southern city of Arequipa, high in the Andes at the foot of the Misti volcano.

His father, Ernesto Vargas Maldonado, left the family before he was born. To avoid public scandal, his mother, Dora Llosa Ureta, took her child to Bolivia, where her father was the Peruvian consul in Cochabamba.

Vargas Llosa said his early life was “somewhat traumatic,” pampered by his mother and grandmother in a large house with servants, his every whim granted.

It was not until he was 10, after the family had moved to Peru’s coastal city of Piura, that he learned his father was alive. His parents reconciled and the family moved to Peru’s capital, Lima.

Vargas Llosa described his father as a disciplinarian who viewed his son’s love of Jules Verne and writing poetry as surefire routes to starvation, and feared for his “manhood,” believing that “poets are always homosexuals.”

After failing to get the boy enrolled in a naval academy because he was underage, Vargas Llosa’s father sent him to Leoncio Prado Military Academy — an experience that was to stay with Vargas Llosa and led to “The Time of the Hero.” The book won the Spanish Critics Award.

The military academy “was like discovering hell,” Vargas Llosa said later.

He entered Peru’s San Marcos University to study literature and law, “the former as a calling and the latter to please my family, which believed, not without certain cause, that writers usually die of hunger.”

After earning his literature degree in 1958 — he didn’t bother submitting his final law thesis — Vargas Llosa won a scholarship to pursue a doctorate in Madrid.

Vargas Llosa drew much of his inspiration from his Peruvian homeland, but preferred to live abroad, residing for spells each year in Madrid, New York and Paris.

His early novels revealed a Peruvian world of military arrogance and brutality, of aristocratic decadence, and of Stone Age Amazon Indians existing simultaneously with 20th-century urban blight.

“Peru is a kind of incurable illness and my relationship to it is intense, harsh and full of the violence of passion,” Vargas Llosa wrote in 1983.

After 16 years in Europe, he returned in 1974 to a Peru then ruled by a left-wing military dictatorship. “I realized I was losing touch with the reality of my country, and above all its language, which for a writer can be deadly,” he said.

In 1990, he ran for the presidency of Peru, a reluctant candidate in a nation torn apart by a messianic Maoist guerrilla insurgency and a basket-case, hyperinflation economy.

But he was defeated by a then-unknown university rector, Alberto Fujimori, who resolved much of the political and economic chaos but went on to become a corrupt and authoritarian leader in the process.

Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante, Vargas Llosa’s longtime friend, later confessed that he had rooted against the writer’s candidacy, observing: “Peru’s uncertain gain would be literature’s loss. Literature is eternity, politics mere history.”

Vargas Llosa also used his literary talents to write several successful novels about the lives of real people, including French Post-Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin and his grandmother, Flora Tristan, in “The Way to Paradise” in 2003 and 19th-century Irish nationalist and diplomat Sir Roger Casement in “The Dream of the Celt” in 2010. His last published novel was “Harsh Times” (Tiempos Recios) in 2019 about a U.S.-backed coup d’etat in Guatemala in 1954.

He became a member of the Royal Spanish Academy in 1994 and held visiting professor and resident writer posts in more than a dozen colleges and universities across the world.

In his teens, Vargas Llosa joined a communist cell and eloped with and later married a 33-year-old Bolivian, Julia Urquidi — the sister-in-law of his uncle. He later drew inspiration from their nine-year marriage to write the hit comic novel “Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter” (La Tía Julia y el Escribidor).

In 1965, he married his first cousin, Patricia Llosa, 10 years his junior, and together they had three children. They divorced 50 years later, and he started a relationship with Spanish society figure Isabel Preysler, former wife of singer Julio Iglesias and mother of singer Enrique Iglesias. They separated in 2022.

He is survived by his children.

___

Giles reported from Madrid.

Franklin Briceño And Ciarán Giles, The Associated Press

-40