New Chief ready for challenges

By Lethbridge Herald on July 9, 2020.

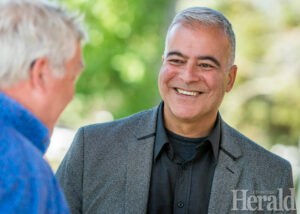

Herald photo by Ian Martens

Newly appointed Chief of Police Shahin Mehdizadeh talks with Mayor Chris Spearman during a visit to the city ahead of taking on his new role later this summer. @IMartensHerald

Herald photo by Ian Martens

Newly appointed Chief of Police Shahin Mehdizadeh talks with Mayor Chris Spearman during a visit to the city ahead of taking on his new role later this summer. @IMartensHeraldTim Kalinowski

Lethbridge Herald

tkalinowski@lethbridgeherald.com

The city’s newly appointed Chief of Police Shahin Mehdizadeh visited Lethbridge on Friday to begin to get a sense for what he is in for over the course of the next few years.

Good natured, quiet-spoken and thoughtful, Mehdizadeh answered questions about the Lethbridge Police Service’s recent turbulence in the wake of the departure of Chief Rob Davis, the defund the police movement, how to deal with systemic racism, and how he expects to take on the social challenges Lethbridge faces during the local drug crisis.

No pressure or anything.

“The challenges in Lethbridge, I don’t think they are unique,” he says, taking on the local crime question first. “Those same challenges exist in every community. When you have drugs, organized crime, what does it take for a police department to make sure the community feels safe? That’s the biggest question.”

Drawing on his 32 years experience as a police officer dealing with everything from undercover work, to community policing, to organized crime and drugs, as well as major crime investigations, in every region of the country, Mehdizadeh says “safety” is his barometer for every decision he makes.

“When you talk about a definition of ‘safe,’ I have to really come and hear from the citizens what they mean by that,” says Mehdizadeh. “I have been in communities where if you have one break and enter in a month, they don’t feel safe. And I have worked in communities when they don’t have a drive-by shooting in a week, they feel very safe. So it all depends on what the community means when they talk about what their definition of safety is, and from there it is working with the community and other partners in the city, and obviously policing is a critical piece of that, as to how we can bring about that sense of safety for the community.”

“The bad news is crime is always going to be there,” he adds.

“We can never have a crime-free environment or location anywhere in the world. But it is how we manage that, and how we actually deal with that, and live day to day so our citizens can get on with their daily activities and enjoy their lives.”

Mehdizadeh says it would be inappropriate for him to speak about the former chief of police or some of the recent internal turbulence the department has been facing. He says he can only go forward, and help the department move forward from here.

“Nobody works for me,” he explains. “We all work for our citizens, because that is actually who is hiring us to perform a duty. Leadership to me isn’t about your rank or title, those things don’t buy you power. Rank and title just give you a level of accountability. The higher you go, the higher the accountability you have. My accountability as chief of police will be to every employee in the Lethbridge Police Service and also the citizens of this community.”

On the subject of racism and prejudice, Mehdizadeh says its something his family is intimately familiar with after having been forced to flee the Iranian Revolution in 1979 because they were not Muslims.

“I lived in New Delhi in India from 1979 to 1984 when we came to Canada,” he explains. “It was May 7, 1984, when we came to the best country in the world, and this country allowed me to make a life for myself. I got married to my beautiful wife in 1993.”

Mehdizadeh feels it’s not his role as chief of police to act as the thought police for anyone else, or even for the officers who he is responsible for in the Lethbridge Police Service, but he has the expectation all officers will carry out their duties at all times without bias and to the best of their abilities, regardless of any personal opinions they may hold.

“There are racist people in society, we know that,” he says. “It is not something that is unknown. And as a result, we are going to have racist people in different organizations regardless of where you work. It’s about how you can manage that. This is a free country; so people have every right to have their opinion if they are racist. You can’t force everyone to love everyone. But the expectation is when they come to work, put their uniform on, and especially in the case of policing, they put all those things in their locker, lock it up, and from there serve every citizen with the respect and dignity they deserve.

“When they go home, they can start hating people as much as they want; I don’t have control over that,” Mehdizadeh states. “But the expectation is every citizen is going to be treated with respect and dignity. But criminals also have to know police have a job to do, and we need to protect other people.”

With the recent discussions about defunding the police, Mehdizadeh says he is curious about what that would mean in application.

“The economics of policing have been a big discussion for many years,” he admits. “It’s an expensive venture. Defunding is a concept I somewhat agree with, but it all depends on what that definition will be. If defunding and removing budget from the police and giving it to other organizations means the police are going to do less now, because often any time there is anything that happens the police get called. We cannot say, ‘No, we’re not going to a scene or we’re not going to go help people.’ So over the years a lot of social issues and problems have come on to the police’s shoulders to deal with. So when you talk about defunding, there needs to be critical discussion if the funds are diverted from the department to other organizations, what is it the police are going to stop doing?

“We (as police) deal with a lot of addiction and mental health issues,” Mehdizadeh adds. “We know, at the end of the day, we are not qualified to deal with these issues. These are major social issues that need other experts to deal with. But, unfortunately, when things happen, we are always the only answer to the problem.”

After 32 years of moving from one post to another in the RCMP, Mehdizadeh says he and his wife are looking forward to putting the rambling life behind them and settling in to be part of their new community in Lethbridge.

“I know I can settle here until I retire from policing, and by that time I may move on to do different things or just be done with it,” he says. “But (coming to Lethbridge) gives me that stability in life to be in one community and serve out the rest of my time as a police officer in this community.”

Follow @TimKalHerald on Twitter

-1