Don’t let others tell your story: McIntyre urges action

By Lethbridge Herald on February 13, 2026.

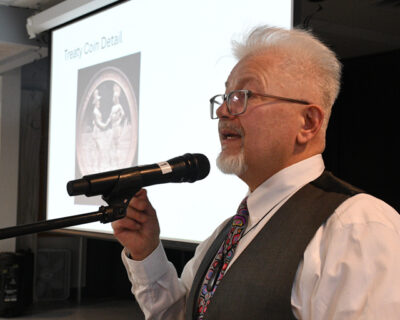

HERALD PHOTO BY JOE MANIO Don McIntyre speaks at the lectern as an image of a treaty coin is projected behind him during his address to the Southern Alberta Council on Public Affairs on Thursday.

HERALD PHOTO BY JOE MANIO Don McIntyre speaks at the lectern as an image of a treaty coin is projected behind him during his address to the Southern Alberta Council on Public Affairs on Thursday.By Joe Manio

Lethbridge Herald

If someone else is telling your story, Don McIntyre says it’s time to speak — and to speak loudly.

The Indigenous governance expert and professor of business management challenged a Southern Alberta Council on Public Affairs (SACPA) audience to rethink ideas many assume are long buried — Manifest Destiny, imperialism, and colonialism — and to recognize how these logics still shape politics, business, and public life.

McIntyre repeatedly emphasized he is not a historian. Instead, he approaches these questions as a scholar of Indigenous governance, business, and the structures of colonialism — studying how historical frameworks continue to influence modern economic and political decisions.

From the start, he framed the discussion through storytelling, beginning with his own identities. Carrying both Ojibwe and Blackfoot names — “Duck with Many Wings” and “Runs with Wolves” — he explained how his names were “summoned into the valley,” connecting him ethically and spiritually to the land and community.

“This tells everybody everywhere I go that I am responsible,” he said, underscoring the importance of reciprocity and mutual care.

McIntyre contrasted Indigenous and Western storytelling. Indigenous stories start simple and grow in complexity with questions and reflection; Western traditions often start complex and are unpacked for comprehension. This approach allows audiences to grasp difficult concepts like imperialism and colonialism more intuitively.

Using a Canadian treaty coin as a prop, McIntyre illustrated how narratives are visualized and simplified. The coin depicts a handshake at its center — a symbol of peace and friendship — yet the figures themselves never existed.

One side shows “empty” European land; the other depicts tipis representing Indigenous homelands. Beneath it all, the underlying title belongs to the Crown, revealing the complexities hidden beneath seemingly simple stories.

He explained imperialism as the drive of empires to expand endlessly, colonialism as the practical occupation of land, and Manifest Destiny as the ideology justifying expansion. Once limited to U.S. westward growth, Manifest Destiny now manifests globally — from Greenland to Venezuela — showing how old logics persist in modern political and economic decisions.

Throughout the presentation, McIntyre encouraged dialogue rather than dictating answers.

“My goal was to have people have the conversation,” he said. “People want to say, ‘I have an opinion. I want to tell you part of my story.’ That is exactly what I wanted to have happen.”

He addressed concentrated power in media and politics, cautioning against passivity.

“As soon as you say, ‘Do we wait for people to take back their stories?’ — there is no waiting. Now is when we have to start to tell our stories as Canadians, as Albertans, that say we’re all in this together. Let’s create a voice that is strong and powerful,” he said.

McIntyre also stressed the ethical responsibilities of citizenship. Drawing from Indigenous governance principles, he highlighted reciprocity:

“I’ve got your back, you’ve got mine,” he said.

Sharing stories strengthens roots, builds community, and allows people to assert their voices in shaping the larger narrative, he said.

Even with decades of study, he acknowledged uncertainty. “I may be the expert, but I have no idea what’s going on. Let’s talk,” he said, inviting the audience into conversation rather than lecturing.

By the end, McIntyre had delivered a framework for understanding how old imperial logics continue to operate, illustrated with images, stories, and principles from his own experience. The takeaway for attendees was clear: the power to control the story rests in their hands.

If that seed takes root, it may not rewrite history overnight, but it could change who feels entitled to tell it — and how.

22-21